"We do not know where dreams come from, but we do know that if we track their mythopoetic images we open to the possibility of aligning the choices of consciousness with the intent of the soul."

—James Hollis, Mythologems: Incarnations of the Invisible World

A (very!) brief history of dream interpretation

The ancients, the gods, and folk theories

At the very beginning of the 20th century, Sigmund Freud attempted to systematize and legitimize dream analysis as a treatment for psychological conditions (at the time, these were called "neuroses"). In The Interpretation of Dreams, he summarizes the history of dream analysis. The ancients, he told us, saw in their dreams a prophecy, a fate handed down from the gods. Dreams predicted future events, and to receive a "bad omen" through a dream was reason enough to tremble and prepare for the end of days.

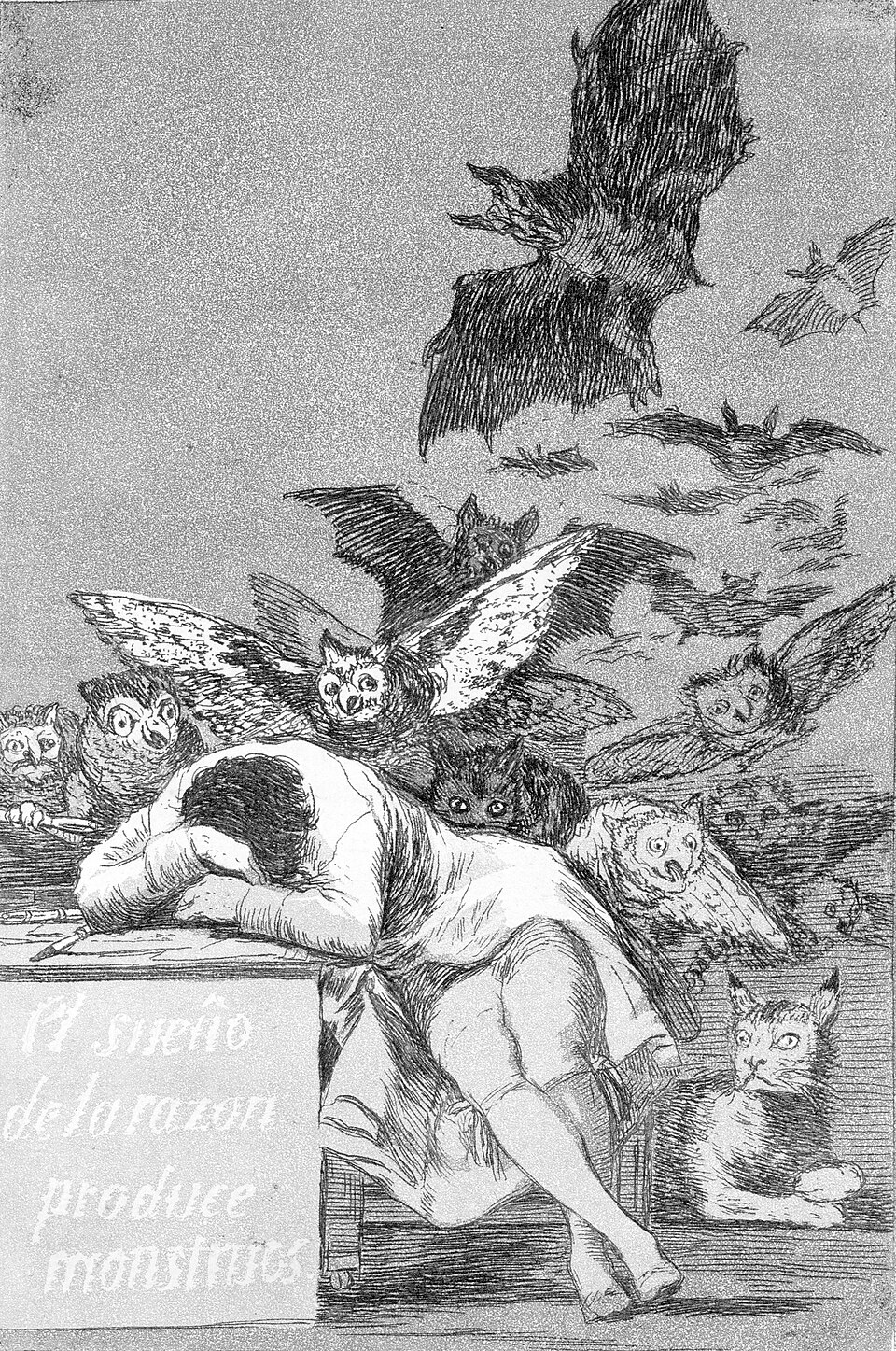

Freud tells us that in Aristotle we begin to see a shift—dreams are no longer reported as the decrees of omnipotent gods, but instead the work of daimons. Daimons, in Greek culture, were intermediaries between the mundane and the divine. They possessed a grounded sense of humanity while also glimmering with supernal light. To Aristotle, dreams were far from absolute. They were subject to the vagaries of everyday life, though they also tethered us to the supramundane. Those who interpreted them properly could encounter transcendent eternal symbols, but they could also be led astray. This notion echoes that of his teacher, Plato, who viewed dreams as distorted, deceptive phenomena — akin to art, and secondary to philosophical reason.

We are told of two popular forms of "folk" dream interpretation in Freud's time: the "symbolic" (but more properly called analogical), and the "cipher method". In the analogical mode, interpreters view dreams as analogies for experiences in conscious life. A dream of a difficult climb up a mountain, for example, may signify the harrowing journey of a man attempting a career in politics. In the cipher method, the interpreter consults a dream dictionary which translates even the most mesmerizing dream symbol into a straightforward word or phrase. A dream of a golden infant simply signifies wealth to come, for example. Both of these approaches are reductive; they fail to comprehend dream symbols as active, dynamic forces, relegating them instead to the curious but ultimately empty signifier.

Freud and "wish-fulfilments"

Freud rightfully saw the limitations of these two approaches and dismissed them. They fail to grapple with the complexities of the psyche that produced such colorful visions, and they reduce the dreamwork to a dreary, clerical task of translation and itemization. His clinical intuition told him that his patients' dreams were much more meaningful than these approaches would indicate, that they were attempting to communicate something vitally important regarding their state of mind.

Unfortunately, Freud developed an approach to dream interpretation which was not only limited and shallow, but also cast the unconscious mind in a murky, shameful light. Through dreams, he speculated, we encounter our secret desires and wishes. Dreams, to him, were wish fulfillments, plain and simple. As the individual is paralyzed in sleep, the conscious mind relaxes its censoring function and allows the unconscious mind to express even its most problematic desires. Through this lens, dreams reveal to us secret perversions, the sadomasochistic or unresolved Oedipal desires that, according to Freud, were the nucleus of all psychological distress.

Though Freud's work did succeed in revealing that dreams were intensely personal and full of subjective meaning, his work could easily devolve into rote categorization of sexual phenomena. And, at their worst, these theories were used to dismiss serious cases of abuse, explaining them away as maladaptive fantasies. We now know that Freud's sexual theories were largely misguided, and as they were the basis of his dream theory, we must see them as historically fascinating but extremely limited in their capacity to understand the psyche.

Jung and the soul

Carl Jung was highly influenced by Freud, and though he found the dream theories very promising, he recognized the limitations of sexual pathologism. Though inspired by the depth of Freud's thinking, Jung's views diverged a great deal. Taking inspiration from spiritualist experimentations and esoteric practices, and rejecting Freud's dogmatism, Jung developed psychological theories that at times thrummed with exalted madness. It took many years of clinical work and self-reflection for this spiritual zeal to be tempered by sober empiricism and the certainty of life experience. The result was a body of work that is profound, transcendent, and sometimes completely baffling.

—C.G. Jung, "Freud and Jung — Contrasts"

It would be impossible to summarize Jung's psychological and philosophical theories here. I highly recommend a reading of Jung to anybody interested in understanding their psyche. A good place to start might be Memories, Dreams, Reflections, which is a fascinating and readable look into Jung's psychological development over the course of his life. For now, I'll summarize a few concepts that are highly relevant to dream analysis:

- Dreams as Compensations: The dream works to balance the psyche as a whole. When we suppress aspects of ourselves in waking life, they express themselves in our dreams. If we are ignoring an important anger, we may have dreams in which we are screaming, fighting, etc. If we have grown out of touch with the playfulness of our childhood, we may have dreams in which a childhood friend invites us to play in the forest. This idea was originated by Jung's friend, Alphonse Maeder. Jung adopted it as a core tenet of his approach to dreamwork.

- Dreams as Mythological Expression: Jung noted that the hallucinations reported by his patients echoed many images from ancient myths. While Freud largely dismissed these mythological contents as primitive expressions of repressed sexual perversions, Jung viewed them as traces of profound psychic activity. Not to be dismissed, he attempted to understand the myths his patients expressed, seeing in them an expression of the soul that transcended pathology. In On the Gods and the World, Roman historian and politician Sallustius says of myths: "these things never happened, and always are [happening]". Jung recognized that myths express the workings of the "collective unconscious", the storehouse of myths and images that we have all inherited as members of the human race, and then tend to reproduce themselves again and again. An individual may use a connection to these myths to see the meaning of their life. If meaning is difficult to find in conscious life, dreams often provide it.

- Active Imagination as a Technique for Insight: Jung experimented a great deal with the symbols in his dreams. Active imagination is a technique he often wrote about and recommended to clients. In active imagination, the individual dialogues with a dream image, taking it to be a real, living thing. At first, this feels pretty silly. But if we can give in to a little play, we will soon find ourselves having deeply meaningful conversations with parts of ourselves we may have neglected, parts which have an important message for us.

- Dreams as Living Symbols: Whereas earlier approaches to dream interpretation, from ancient "oneiromancy" to Freudian analysis of sexual pathology, did little more than translate dream images into fixed, conscious contents, Jung saw the images in dreams as true, living symbols. In Psychological Types he explains that "a symbol really lives only when it is the best and highest expression for something divine but not yet known to the observer. It then compels his unconscious participation and has a life-giving and life-enhancing effect" (C.W. vol. 6, §819). When we interpret a dream, then, we are not attempting to "resolve" it, to reduce it to a simple series of facts. Instead, we are learning to speak to these symbols, to allow them to express themselves through us.

Jung's major contribution to dream interpretation was his steadfast, almost religious reverence for dream contents as sources of revelation and psychological/spiritual wholeness. In a sense, this was a return to the "daimonic" aspect of dreams expressed by Aristotle, but with greater emphasis on the daimon's link to the divine. He understood the nature of the symbol as few before him had. After all, we could easily ask Freud or the ancients: why do dreams provoke us with such florid images? Freud could explain why these images had become repressed, but when asked about their peculiarly mythological contents he resorted to his old canards about Oedipus and perversion. Freud had seen in the Oedipus myth a resonant image, but this resonance to him signalled nothing other than a universal tendency towards neurosis. Jung saw in myths and dreams the exact opposite: an innate drive towards psychic wholeness, an ineffable spiritual momentum that needed only to be heard and received.

Writing of a dream his client had reported, we see the solemn reverence of a devotee and the conviction of an individual who had felt the living symbols down to his bones:

—C.G. Jung, Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious, C.W. vol. 9, §399

My approach to dream interpretation

Though highly influenced by Jung's thought, I have developed my own idiosyncratic approach to dream interpretation, having analyzed hundreds of dreams myself. I find that Jungian analysis is illuminating and profound, but at times it can also be burdensome. To paraphrase Jung himself, everything that emits light also casts a shadow. The "shadow" of Jungian analysis to me is its extremely high learning curve and reliance on obscure scholarship. Jung, like anybody, was a product of his time. He was learning and studying at a time when all German students learned Greek and Latin, recited Goethe from memory, and read the Bible daily. This is not my cultural background, and it is not the background of almost anyone I meet in the United States. For those of us who grew up "reading" I Spy books, watching Dragon Ball Z and flash cartoons, and spending hours playing Roller Coaster Tycoon instead of studying Thomas Aquinas, Jung's works are at first completely impenetrable. To the 21st century American, Faust and Zarathustra are dim, obscure figures from the past. To Jung, they were brilliant expressions of the psychological process. This gap is a difficult one to bridge.

This is not at all to say that understanding these mythological sources is not useful. I have spent many hours studying these myths myself, and I find it rewarding and exciting work. It may even be vitally important at times. But not everyone will resonate with Paracelcus, psychic mediums, or Swedenborg, as Jung did. In fact, it is fair to say that Jung's disappointment in his shallow, unreflective Christian father is what inspired his often painful pursuit of spiritual meaning.

All this is to say that we can allow our own feelings and intuition for dream symbols to take precedence, invoking mythological frameworks only when our own intuition struggles to make headway. Jung himself stated that one's personal associations with any given dream image should always be the starting point. So, are topics like alchemy, Egyptian myth, and mandalas fascinating? Absolutely. Are they necessary? In my opinion no, not really — certainly not for everyone.

We live in a time in which too many important concepts are trivialized on social media platforms. Alchemy and mysticism, when not studied with sincerity, often degenerate into shallow aestheticism, New Age "positive psychology", irrational occultism, or maybe the worst of them all... branding. I take care to treat ancient symbols with reverence to counterbalance this casual and even reckless attitude towards spirituality. And let's be honest: some of the blame here may be placed on the original authors, many of whom admitted openly to obscurantism. In light of this, I am not here to demonstrate pretentious academic rigor. My job is not to burden you with obscure references, but to invoke them when they're useful. Ancient symbols should serve us, first and foremost. They may be discarded when they become leaden and mute.

The process

When you bring a dream to me, I treat them as works of literature. I have a background in literary analysis, and I see dreams as fantastic stories. I look for themes, patterns, and symbols. Beneath the surface of even the murkiest dream is a lucid, coherent structure. In fact, I've found that the stranger a dream appears to the conscious mind, the more meaningful it tends to be. I reflect on the dream, allowing it to work "on me" for a little while. I trust that symbols will arise, that the dream will slowly illuminate itself.

Once I have a (provisional) symbolic schematic to the dream, I use my knowledge of psychology and the individuation process to see where the dream is pointing. Dreams nearly always point towards an evolution, a powerful challenge that often results in profound growth. I attempt to elucidate this challenge and offer experiments to work with these images further. These may be simple prompts for reflection, or active imagination exercises. My goal is never to "fully understand" a dream, but to learn to speak its language.

"A suitable warning to the dream-interpreter—if only it were not so paradoxical—would be: Do anything you like, only don't try to understand!"

—C.G. Jung, "Dream Analysis and its Practical Application"

All dreams expose luminous surfaces that expand infinitely in every direction. Symbols, as discussed above, are important because they elude a fixed meaning. My job is to help the symbols speak, and to help you to speak with them, allowing them to express their transcendent contents. I am not at all an authority on the meaning of your dream — the dream is always yours, and I welcome you to disagree with my ideas whenever it feels I have gotten it wrong. I trust your spirit to feel into the dream and understand it as much as you would like to. It takes wisdom to interpret a dream, but it also takes wisdom to know when to let it rest, when to refuse to scrutinize a symbol whose feelings may transcend conscious thought. We simply cannot do everything with language.

I only hope to clarify confusion, and to offer a safe, reflective space in which the images of your soul are treated with respect and dignity. My goal is not to be an "expert", but to help you to understand your dream language to the point that, if I do my job, you will be able to do much of your dreamwork on your own.

There are too many bad dreams. What makes a dream "bad" is not that it scares us, but that we fail to see its meaning. When we begin to understand symbols, our nightmares may become good for the soul. They could even be vital.